When Manu and Sandra asked me to come with them to climb the Llullaillaco volcano in Argentina’s NOA region, I thought twice. Volcanoes aren’t really my cup of tea…..the endless climbs, the difference in altitude, the rocky terrain….bref, I swore I’d never do them again. Then I remembered the beautiful expedition to the Ojos del Salado and the Pissis on the Argentinian side. The landscapes there were splendid, deserts, salars, colours….and I’d also been dreaming of going to the NOA and Salta for a long time. So it was a go for Socompa (6048m) and LLullaillaco (6739m)!

This expedition was a wonderful experience, full of colour, exchanges, history, laughter and suffering on the slopes of volcanoes. A perfect cocktail for a fantastic two weeks!

Take a look at the 17-day programme I’ve put together for you following my exploration:

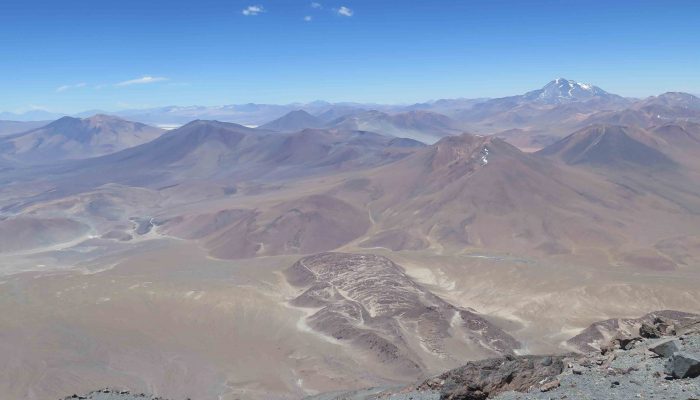

The Puna region lies to the west of Salta, on the border with Chile. The “Puna” (“high land” in Quechua) consists of high Andean plateaux with an average altitude of 3,700m. It’s an arid region, with temperatures varying by more than 40 degrees between day and night (20ºC maximum and -25ºC at night). The rare rains are concentrated in summer and can cause a climatic phenomenon known as the “Andean winter”, with rain, hail and snow in the middle of summer.

You feel alone in the world, surrounded by salars, deserts, lunar landscapes, lagoons and surprising colours. The people of San Antonio de los Cobres and Tolar Grande will give you a warm welcome, despite the difficult living conditions.

The only human presence in these desert areas is the Cloud Train railway line. This line was built in 1921. The aim was to link the railways of Chile and Argentina, in order to facilitate trade between the two countries, and in particular the supply of Chilean miners, whose numbers were steadily increasing, mainly thanks to the growth in the extraction of saltpetre (sodium and potassium nitrate salts). The euphoria of the time led those in charge to calculate that the work would be completed in 6 years, but the reality was quite different: it wasn’t until 1948 that the Salta railway joined the Chilean railway at Socompa, at an altitude of 3,800m. The struggle against the natural barriers was terrible, and the construction of the railway was a real challenge at the time. The railway has 29 bridges, 21 tunnels, 13 viaducts, two spiral loops (a railway technique for climbing steep gradients) and two zigzags. For more practical information, click here:

http://www.trenalasnubes.com.ar/noroeste_argentino/turismo_salta/es_tren_a_las_nubes_recorrido.aspx

Our route from Salta followed this railway line all the way to the Socompa border. We could then imagine the work required to build this titanic structure. It’s just incredible. Difficult to maintain, only a small part of it is in operation for tourists from San Antonio de los Cobres (to and from the Polvorilla viaduct at 4220m).

A goods train runs once a week to the Socompa border. It started operating again a year and a half ago. It’s a great moment for the Socompa carabinieri! Idle and isolated in their ghost station, the carabinieri came to chat with us. Surprised and happy at our presence here, they told us that hardly anyone climbs to the top of Socompa, as it’s too hard physically! I think they were referring in particular to Sandra and myself….we dared to say shyly that we were mountaineers, hoping all the same that we would be able to reach the summit. The ascent of the Macon volcano, which rises to 5500m on the outskirts of Tolar Grande, went off without too much trouble, despite the 1100m difference in altitude. But the Socompa volcano looked like a big one!

So first we climbed up onto a rocky promontory at the foot of a glacier tongue. This was a tiring exercise, as the logistics were not straightforward. Very few porters work in this region. The car leaves us at 4400m altitude, the porters carry the food and water, while we have to load all our personal equipment at the high camp at around 5000m. The view from our vantage point is breathtaking. After a decent night’s sleep, shall we say at this altitude, we set off into a rocky chaos by headlamp. We climb straight up the mountainside to reach the ridges at around 5400m. The climb through the rocks is not as easy as expected. From here, we pass behind the rocky bar via a steep passage to reach an amphitheatre at 5500m. It’s a sheltered, pleasant spot, ideal for a break. But we mustn’t delay, as we’re barely halfway up the ascent. The climb continues over sand and rocks. I set off on the snowy section below a pass that seemed to lead to the summit (or near summit!), hoping that progress would be easier. In the end, we have to return to the strip of land, as the penitents are just unbearable! From there, we had to choose between soggy, heavy sand or unstable rocks. Suffice to say that the last 200m of ascent were terrible. After a final pass, we had 50 metres left in the rocks, which were a real torture. I reached the summit at 6048m, exhausted but happy. That’s it! Pichi, our guide, tells us that tourists who do the Socompa don’t do the LLullaillaco, because they wear themselves out on the Socompa. We’re beginning to realise that our choice of volcanoes was not the wisest one, and we had indeed wasted some time on this volcano_….

Impossible to have a rest day at Socompa station….it’s 50ºC in the tent. So we set off for the water valley (Quebrada del agua) before reaching the LLullaillaco base camp. This is the only place where you can find drinking water, a 20-minute drive from Socompa, not far from the Socompa Lagoon. A stream runs down the valley, as if by magic in this desert. In the 1940s, this was the last train station before the Socompa border. On the hilltop, a luxurious house stands as a reminder of a glorious era. A wealthy owner ran the station. Down below, close to the river, a village lies virtually untouched, hastily abandoned. A whole family, the ‘Alegre’ family, lived there happily and well, it seemed. With a little time to spare, we set off to discover the village and its history. We eventually found an open door, and were astonished to discover a cosy interior dating back to the 40s and 50s. Everything had been left as it was: sewing machines, a ‘Colombia’ gramophone, letters, photos….these people lived in comfort despite the difficult climatic conditions. They also travelled a lot, if we are to believe the incredible photos dating from 1938 to 1946. This discovery was incredible. I felt excited, as if I’d been transported back to my childhood readings of the “Club of 5”!

After an invigorating dip in the Quebrada del Agua stream and a supply of drinking water, we set off for the long-awaited LLullaillaco base camp. This volcano is majestic and steeped in history.

In 1999, a National Geographic expedition co-led by Constanza Ceruti and Johan Reinhrad, a specialist in Inca civilisations, discovered 3 children’s mummies beneath the summit of LLullaillaco. For further information, visit

http://www.nationalgeographic.fr/histoire/les-enfants-incas-etaient-drogues-avant-detre-sacrifies

The Llullaillaco volcano was the scene of one of the most important ceremonies in the Inca ritual calendar, the Capacocha. In 1999, the mummies of a 6-year-old boy, a 7-year-old girl and a 15-year-old girl were discovered beneath the summit of Llullaillaco. It has become one of the most sacred sites in the Andes. The ruins, located at an altitude of 6,520m, are the highest archaeological site in the world. The site is steeped in history and belief. This makes it one of the most sacred places in the Andes.

In these rituals, which united sacred space with ancestral time, it was customary to offer the best of oneself in order to obtain the benevolence of the gods in return. Changes in the political order, natural phenomena or the agricultural cycle could be events that motivated these religious activities.

From the base camp at 4,902m, we climbed up the slopes of the volcano to Camp I at 5,400m. The ascent is fairly leisurely in the sand. The first camp is very beautiful, nestled in a hollow, protected from the winds, at the foot of a field of giant penitents. This camp is very pleasant and provides a good rest before the climb to over 6000m. The view of the summit is breathtaking. The climb continued without any major difficulties, apart from a small snowfall that greeted us as we reached the high camp. It was very surprising and unpredictable after 8 arid days without a cloud in the sky! We prayed that the weather would improve the next day. We set off around 5am under a starry sky, so we were well motivated to make the climb. The ascent is via the southern ridge, in a rocky chaos. The climb is very tough. There is no real path. The rock slides under our feet. The slope also gradually becomes steeper, and the boulders bigger and more unstable. It’s a real hell getting up to the summit. The entrance is via a steep corridor between two rocky peaks. A quarter of an hour before reaching the col between these two peaks, the sky was still blue. Some clouds had arrived, but it was more of a mist that rose towards the summit and quickly disappeared. Just as we passed the pass and reached the sacred ruins, a mini hailstorm descended on us. It came suddenly, without warning, like a divine message. We made an offering to the Pachamama, thinking that perhaps we should have done so before asking permission to climb to the summit! The ruins are impressive, nestling at an altitude of 6520m, just below the now very close summit. Pichi wouldn’t let us go any higher. The last few metres in the fog with no visibility made no sense. What’s more, bad weather can strike quickly in these parts. Pichi told us that some tourists had been stuck in a snowstorm for several days, having to abandon the car that had been stuck for three months under the snow at the base camp. We went down a bit disappointed, but happy to have discovered the sacred ruins and to have made this great expedition. Once back at the base camp, the sun and the heat returned…..the sacred mountain hadn’t wanted to open its doors to us!

Once back in Salta, we learned that a storm had hit Salta and the surrounding area, taking out a bridge on the railway line. In the end, it may just have been the climatic phenomenon known as the ‘Andean winter’, aggravated by climate change. Divine message or climate change, whatever the case, we enjoyed a delicious entrecote steak with malbec sauce on our arrival in Salta!

Once back in Salta, we learned that a storm had hit Salta and the surrounding area, taking out a bridge on the railway line. In the end, it may just have been the climatic phenomenon known as the ‘Andean winter’, aggravated by climate change. Divine message or climate change, whatever the case, we enjoyed a delicious entrecote steak with malbec sauce on our arrival in Salta!